Scotch whisky on the table in trade talks with India

- Trade talks between the UK and India are now under way, with Scotch whisky on the table as one product with huge potential gains.

- Experience of failed talks with the EU point to many obstacles to cracking the world’s biggest whisky market, going beyond the 150% tariff.

- Scotch is only one product among many that Britain wants to export more, including finance and cars, but the compromises required with India’s demands could be difficult for the UK Government.

A bottle of Scotch whisky arriving in the port of Mumbai faces a colossal 150% import tariff, yet it hasn’t stopped Indians from being enthusiastic drinkers of a dram.

India is the world’s biggest market for whisky, most of it termed “Indian-made foreign liquor”. The big brands sound more Speyside than sub-continental: McDowell’s, Royal Stag, Bagpiper, Peter Scot.

Domestic distillers have lobbied fiercely and successfully to limit Scotch imports. If the bottle is sold in Mumbai or elsewhere in the state of Maharashtra, it used to carry a further 300% tariff, though that was recently halved.

Among other parts of the Indian union, some don’t allow alcohol sales at all, except to those who know how to get round the rules.

Scotch makes up only 2% of India’s market. Yet the value of Scotch whisky sales to India has risen from below £60m in 2011 to more than £150m in 2019. That has been on the soaring growth of the economy and the country’s burgeoning middle class, with its drouth for prestige international products and brands.

By volume, last year saw India become the third biggest market for Scotch. But as 60% of that is in bulk, for bottling in India or for blending with local spirits, that is lower value Scotch than exported to other markets.

Unpredictable rules

So imagine what could be sold with lower tariffs. There’s a big prize from getting them removed, or at least slashed. And that puts whisky firmly on the table of the talks, which began this week, aimed at a free trade agreement between the UK and India.

Oxford Economics doesn’t imagine what could be sold: it models it. Commissioned by the Scotch Whisky Association, it assumes that the import tariffs come down to around 25%.

With that, it estimates £1.2bn more exports within five years, and that could generate 1,300 jobs in the UK.

And part of the pitch to the Indian government is that such trade liberalisation would only take Scotch from 2% to to around 6% of the nation’s consumption, while boosting Delhi’s government revenues by more than £3bn. That way, everyone wins.

But trade liberalisation isn’t that simple, particularly in India. One of the first problems is getting to an agreement on the valuation of an import consignment before it even leaves the port. That can take a very long time, and a free trade deal would have to simplify that process.

The application of rules can be, let’s say, unpredictable. One key part of any free trade deal would be a court of arbitration. But as Edinburgh-based Cairn Energy found (it recently rebranded as Capricorn), such existing international rules on investment can get stuck in Indian bureaucracy and legal obstacles.

Having developed the country’s biggest oil field and sold its stake, Cairn’s attempts to reclaim at least $1bn owed by the Delhi tax authorities only began to make progress after it started action to seize the government’s overseas assets.

Lost empire

After leaving the port, imports of whisky into India then hit 30 different markets, across India’s states, requiring different labelling, with different duty and retail rules. Some states have a government monopoly in retailing alcohol, which is open to abuse by those in power.

Those in the distilling industry who have been trying to break down the barriers to trade have low expectations of those internal trade barriers being removed under a deal between the UK government and the federal trade ministry in Delhi.

A deal between national governments would be a big breakthrough, but just the start of a new chapter in trying to crack this market.

After 10 years of the European Union trying, but failing, to get a free trade deal, in which Scotch whisky also played a prominent part, there is some optimism that the mood in India has shifted.

A crucial part of that is that the domestic distilling industry now has more international ownership.

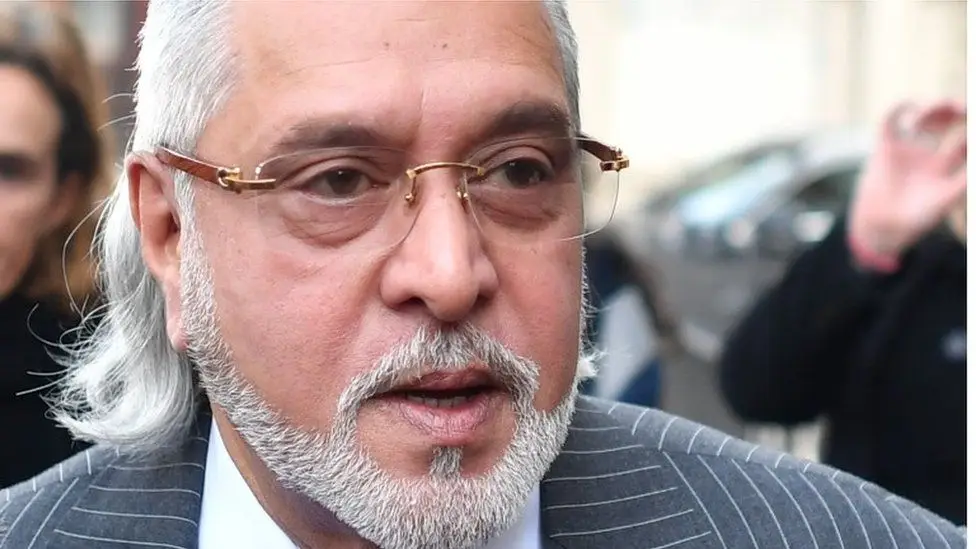

The flamboyant businessman Vijay Mallya, who bought Scotch distiller Whyte & Mackay to add to India’s biggest distiller, United Spirits – along with his empire of brewing, a large airline, premier league cricket, a Formula 1 team and a seat in India’s parliament – is out of the picture now. Living in London, the sun has set on his empire, and he is fighting extradition to his homeland to face charges of money laundering on a vast scale.

Much of United Distillers is now owned by Diageo, the London-headquartered global drinks giant which happens also to own around 40% of Scotch production.

So it is now a big player in Indian distilling and in Scotch, plus gin, tequila, rum and Guinness, which it would dearly love to get into the Indian market. By no coincidence, Indian distillers seem to be putting up less lobbying resistance to imports of Scotch.

Skills and flair

So could this now be the breakthrough for Scotch into the world’s biggest whisky market?

The UK government, with a new-ish trade secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan, is eager to show progress post-Brexit on reaching beyond European trade to “Global Britain”. There isn’t much prospect of a breakthrough deal anywhere else.

Whitehall brings inexperience to the table, while India’s trade negotiators have lots of experience, much of it in refusing to compromise due to domestic politics and an under-current of belief that India can be self-sufficient.

The trade talks are likely also to feature the desire of Britain’s financial sector to get into the Indian market, to which it currently exports only a 10th of its sales to Japan.

That would require dismantling of massively complex regulatory barriers.

Its lead trade body, CityUK, wants to see fewer restrictions on data flows, and visas for British nationals to work at least temporarily in India. Having seen Cairn Energy and others snared, it is also seeking protection for investments.

The car industry, including Indian-owned Jaguar Land Rover, wants to get access to wealthy customers on the sub-continent.

And India has its own negotiating priorities, starting with much lower barriers for its professionals to work in the UK.

Its view of world trade is the projection of the power of the Indian diaspora – a huge English-speaking pool of technical skills and entrepreneurial flair.

But welcoming many more Indians into Britain could be seen as running counter to the spirit of Brexit, which was to keep foreign workers out.

That would be a tricky political compromise for the UK government to sell to its supporters. It’s one that the Home Secretary, Priti Patel – herself a daughter of that Indian diaspora – is reported to be firmly against.