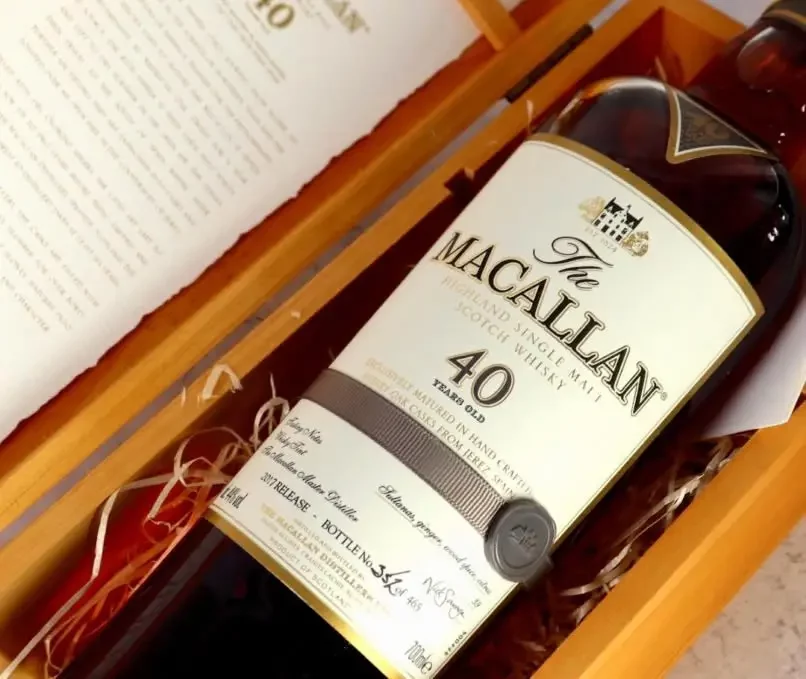

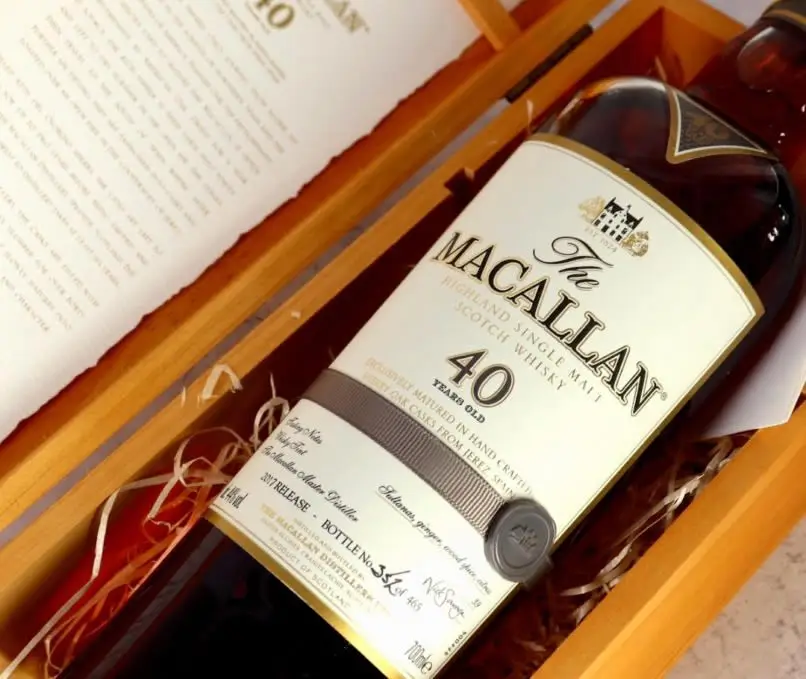

A bottle of Scotch whisky arriving in the port of Mumbai faces a colossal 150% import tariff, yet it hasn’t stopped Indians from being enthusiastic drinkers of a dram.

India is the world’s biggest market for whisky, most of it termed “Indian-made foreign liquor”. The big brands sound more Speyside than sub-continental: McDowell’s, Royal Stag, Bagpiper, Peter Scot.

Domestic distillers have lobbied fiercely and successfully to limit Scotch imports. If the bottle is sold in Mumbai or elsewhere in the state of Maharashtra, it used to carry a further 300% tariff, though that was recently halved.

Among other parts of the Indian union, some don’t allow alcohol sales at all, except to those who know how to get round the rules.

Scotch makes up only 2% of India’s market. Yet the value of Scotch whisky sales to India has risen from below £60m in 2011 to more than £150m in 2019. That has been on the soaring growth of the economy and the country’s burgeoning middle class, with its drouth for prestige international products and brands.

By volume, last year saw India become the third biggest market for Scotch. But as 60% of that is in bulk, for bottling in India or for blending with local spirits, that is lower value Scotch than exported to other markets.